The War of Return is a book written by two self-described “prominent Israeli leftists” that makes a bold claim in its subtitle: “Western Indulgence of the Palestinian Dream Has Obstructed the Path to Peace.”1 The book was originally published, in Hebrew, in 2018. The English translation debuted two years after in 2020. Three years later, and three months after the October 7th attacks, those who hope for peace seem to have more reason for despair than ever. I read War of Return hoping for a fresh perspective. So together, let’s turn to co-authors Adi Schwartz—an Israeli journalist formerly at Haaretz, the country’s largest left-wing newspaper—and Einat Wilf—a former Labor party politician—to discuss “the single largest obstacle to lasting peace” and how we might go about solving this seemingly intractable conflict capturing the attention of the world.2

The Narrative of the Conflict, as Recounted in War of Return

You Probably Think You Know What the Arab-Israeli Conflict Is

The Arab-Israeli conflict, stretching now for over seven decades and continuing to impact the lives of millions of people throughout the Middle East, has had numerous near misses with peace. This is because of a fundamentally incorrect assumption often held by Israeli and Western negotiators that “this [is] a territorial conflict that [can] be solved by partitioning the land into two states, that the Palestinians only [want] a state of their own in the territories, and that the Israeli occupation and the settlements [are] the primary obstacle preventing peace.”34 According to Schwartz and Wilf, they have misunderstood the problem.

In reality, our favorite co-authors say, this is an ideological conflict over the very existence of Israel. It is an absolute rejection of minority sovereignty in a region dominated by the Arabs, and it is not new: “…the belief that Zionism was an outrageous injustice predated the war and caused the Arabs to violently oppose the Jewish national liberation movement many decades earlier.”5 The territorial framing of the conflict is thus not conducive to a solution—no state, with any borders, will appease a movement that feels like partition itself is an injustice.

…this was not a conflict between two national movements, each seeking first and foremost its own independence, but rather about one group (the Arabs) seeking first and foremost to foil the independence of another (the Jews).6

What Does That Have to Do with Refugees?

Palestinians’ claimed right of return, in the minds of Schwartz and Wilf, is a deceptively named aspiration to negate Jewish self-determination. There can be no democratic Jewish sovereignty where Jews are a minority.7 It is thus that the Palestinian right of return is “not merely about moving ten or twenty miles to homes left behind, but primarily about returning to the time before the terrible defeat of the Nakba and the establishment of the state of Israel,” by making Jews a minority in their own homeland.8 In essence, it is about rewinding history and undoing the creation of the Jewish state.

I myself misunderstood what was meant by “right of return” before reading this book. As the phrase is used, the right of return is the right of Palestinians to return not to a future Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza—as I had believed, and supported—but in fact, to the sovereign state of Israel. Return “could only be realized in the territory of the state of Israel atop the ruins of the Jewish right of self-determination.”9 To mandate a right of return to Israeli territory is to reject “the principle of territorial partition” and a two-state solution.10

War of Return attributes the creation of the refugee issue to this rejection of the two-state solution by the Arabs. They argue that if the Arabs had accepted partition in 1948 and established a state of their own, no one would have been displaced:11

…it is a fact that the departure of the Arabs was a result of the war and only of the war. Before the Arabs waged war against partition, they did not leave their homes. The Arab flight and the refugees from the war were neither inevitable nor necessary nor inherent in Zionism.12

The blame for the displacement of the refugees, they claim, is unflinchingly on the shoulders of the Arabs, not the Jews. No one is entitled to the status quo ante:

Those who wage war to eliminate another people, and to prevent their achieving independence, cannot legitimately complain that “they suffered an exceptional injustice” when they lose and flee the land.13

Furthermore, according to Schwartz and Wilf, the legal right of return simply does not exist: “No legal obligation or treaty existed that… obliged Israel to let [Palestinians] return to its territory” in the aftermath of the 1948 war.14 Flight and expulsions occurred throughout the 20th century, including during this seminal war. Indeed, unlike in Israel where an Arab minority remained after the war, “not a single Jew remained in the areas conquered by Arab forces.”15

How can it be that the Palestinian refugee problem still exists 75 years later, and at a greater scale than its start? “The answer to why the Palestinian refugee problem still exists lies neither in the conditions of its birth nor in its scale nor in the number of victims: nothing here is unique. The answer must lie elsewhere.”16 That elsewhere, War of Return posits, is in the refusal of the Arabs “to solve the [conflict] by creating a new status quo in the Middle East” in which Jews and Arabs could have exercised self-determination side-by-side—which was accomplished through the political manipulation and exacerbation of the Palestinian refugee issue.17

The Tragic Ensuing Decades

Schwartz and Wilf argue that the critical issue is the Palestinians’ demand for return to Israel. Progress toward peace is made on all fronts but return, the “one article that Israel [can] absolutely not agree to, as it [entails] its very suicide.”18 Return is instead silently propped up by Arab support—all but guaranteeing a continued, violent existence for Palestinians and all others in the region. Promising initiatives to resettle hundreds of thousands of refugees in the immediate aftermath of the 1948 war, in the Jordan Valley and the Sinai, went nowhere. The “biggest rehabilitation project of the 1950s for Palestinian refugees,” a farm run by Musa Alami (a prominent Palestinian nationalist), employed thousands of Palestinians in the Jericho area—with a specific focus on orphans of the war—and grew orchards and productive crops over thousands of dunams, with export contracts to Saudi Arabia, fifty wells, and a school.19 It was leveled in 1955 by Palestinians believing its existence would help “enable the resolution of outstanding political disputes between the sides.”20

The refugee issue, claim Schwartz and Wilf, is cynically manufactured and perpetuated by Arab leaders. The long-term adoption of the position that “improving the living conditions of a few hundreds of thousands of refugees [is] less important than their war with Zionism” has led the Arab world to the creation of a Palestinian refugee-hood that is completely divorced from the experience of every other refugee group.21 Indeed, Palestinian refugees are not governed by UNHCR, the UN agency for refugees, but by their own temporary commission—UNRWA—the regular extension of which “has become a quasi-automatic annual tradition” at the United Nations.22 War of Return devotes a great amount of effort to describing how UNRWA “was transformed from being a failed agency for refugee rehabilitation to a very successful organization for” halting progress in the Middle East.23 “For decades,” Schwartz and Wilf say, “UNRWA has sustained a parallel world of policy and executive decisions that serve the Palestinian narrative alone,” and leave the Middle East in a radicalizing limbo that actively works against peace.24

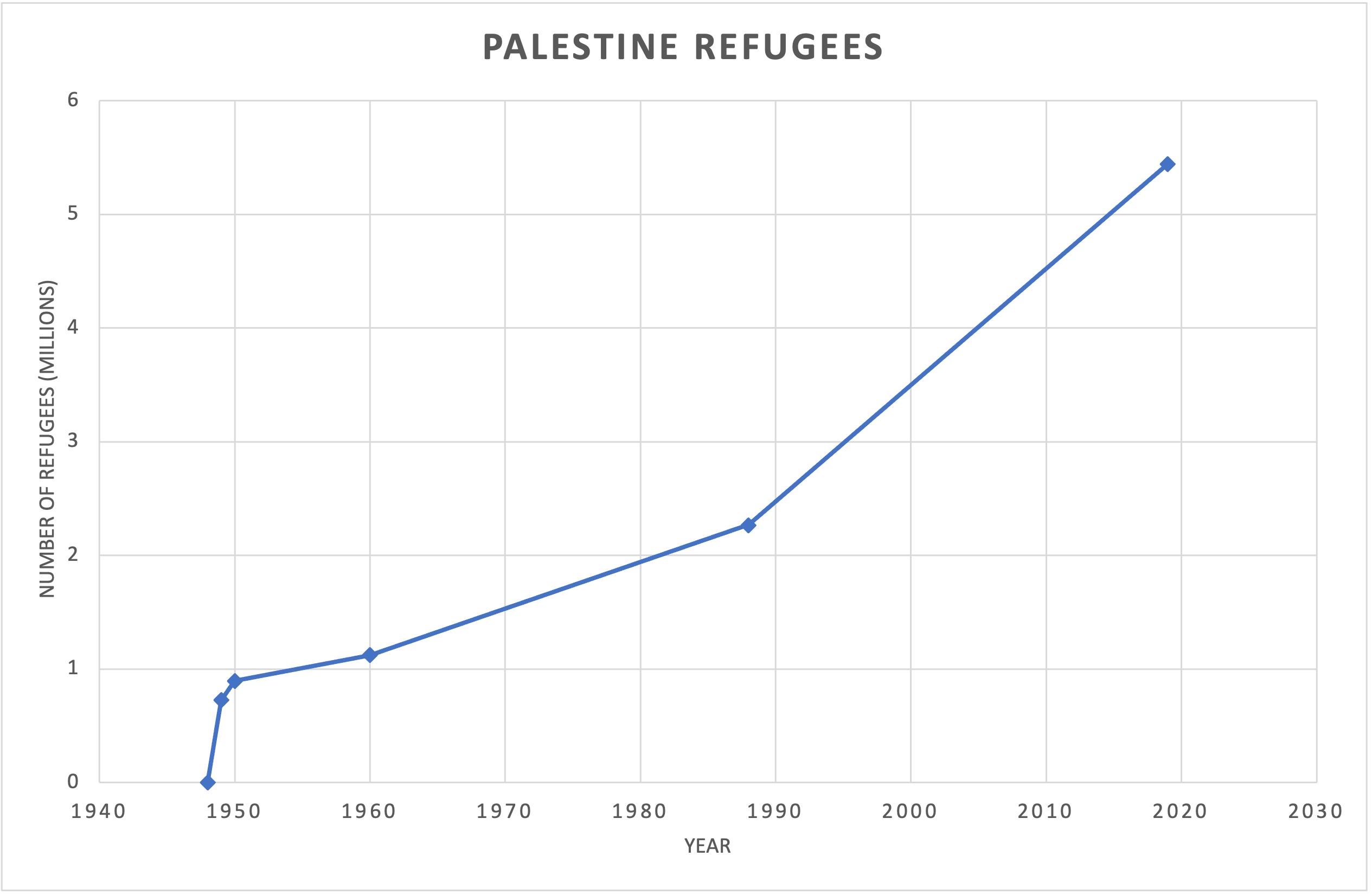

The list of UNRWA oddities is very, very long. Unlike all other groups, UNRWA’s “Palestine refugee” status is hereditary—resulting in a registered population of over 5 million people from an initial group of approximately 700,000 displaced Palestinians (see chart below). Unlike all other groups, refugee status is not surrendered when additional citizenship is achieved; indeed, 2.2 million UNRWA-registered refugees are citizens of Jordan, but they retain their “refugee” status. Astoundingly, these refugees make up 70% of Jordan’s population: “It is difficult, bordering on impossible, to get a consistent answer from Jordanian officials to the question of how the Jordanian state sees its own citizens.”25 Another 2.2 million UNRWA-registered refugees live in the West Bank and Gaza, territories allocated for the future Palestinian state, making them refugees within their own future state. An additional million are officially split between Syria and Lebanon, territories where “most of them do not even reside… anymore.”26 Since the 1960s, “most of the [Palestinian] refugee camps were neighborhoods of the Arab towns next to which they were built,” with housing markets and daily realities entirely different from the Western image of vast, impoverished tent cities.27 Within these refugee-camps-that-are-cities, Western-funded UNRWA-run schools teach students “a narrative of victimhood, based on a singular, striking injustice,” which have resulted over time, Schwartz and Wilf believe, in a direct connection between “the perpetuation of UNRWA for political reasons to the emergence of” Palestinian terrorism.28 Thus, according to Schwartz and Wilf, the purpose of the continued use and expansion of refugee status in this situation is to perpetuate and reinforce the Arab claim toward the right of return and its inherent goal of eliminating Israel.29

So, Should You Read It?

The War of Return is worth reading, but is difficult to synthesize. The book is disorganized: it has a message it wishes to impress upon you, but is not sufficiently clear and driven in doing so. It is without a doubt the most thoroughly cited book I have ever encountered. A full third of its page count is dedicated to footnotes and bibliography alone.30 In an issue swimming in contentious Instagram infographics, Schwartz and Wilf have brought the receipts.31 In doing so, however, they interweave theory, history, and proscribed solutions in a manner that leaves the reader with a significantly improved understanding of the conflict but great difficulty summing up this new knowledge. The book desperately needs a more linear structure.

Additionally, assertions about Palestinian thought are found throughout the book and can be difficult to prove true or false. How would one go about assessing the claim that “the Palestinians’ commitment to the idea that they are still refugees and also possess a right of return to the state of Israel is deeply embedded in the Palestinian identity and its collective ethos?”32 Schwartz and Wilf proffer that it “is an issue on which no Palestinian political opposition or dissent exists,” which is perhaps as good a proxy as you will find.33 I don’t necessarily doubt that it is correct that there is a cultural narrative of “perpetual injustice” in the Palestinian camp, but I am cognizant of the fact that it is difficult to prove definitively. The book’s arguments are made weaker by their occasional reliance on alleged Palestinian beliefs, as opposed to evidence of action.

Furthermore, the book’s critique of the West—which we are led to believe by the subtitle will be severe—is, in essence, that it has failed to sufficiently counter anti-Israel extremism in the Arab world. The book makes a compelling argument that this is the case, and that “geostrategic interests” (read: oil) have muddled what would otherwise be clear opposition to an ideology that seeks to eliminate a UN member state.34 Still, this strikes me as a somewhat confusing target for criticism in this case when it may be more appropriate to condemn the Arab extremists themselves.

With that said: this book managed to significantly change my thinking on the conflict. As someone who thinks about this a fair amount, I would consider that on its face to be a significant endorsement. If that’s not enough of an endorsement, here’s another one: you should probably read this book. I now realize that I did not at all understand the Palestinian refugee issue before reading this book, and in its aftermath feel confident and prepared in its discussion. Schwartz and Wilf did not challenge my fundamental view of the conflict, but they gave me a much clearer understanding of the refugee issue, which has profound implications.

The War of Return has been a timely read ever since its publication. Indeed, in the ensuing years, very few of the foundational facts and conditions it addresses have experienced any shift; the Arab-Israeli conflict had reached somewhat of a standstill.

It is the “fervent hope [of Schwartz and Wilf] that in writing this book [they] contribute in a meaningful way to real and lasting peace.” As such, their proposals need adjustment.35 With the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas War in the aftermath of October 7th, there is potential for a serious shift in the history of the conflict.

After the war is over, there may be an opportunity—for the first time in a long time—for meaningful change. The parties must move quickly to final-status negotiations, to bring a conclusion to the violence that has plagued our peoples for decades. We can no longer think about slow change. Two states, for two peoples, as originally envisioned by the United Nations in 1947 as “lawful, moral, and legitimate” solution.36 In order for that to happen we must be guided, in part, by the book’s total refusal of the right of return:

When Palestinians complain that recognizing a Jewish state means relinquishing the right of return, the response should be, “Yes, that is exactly what it means.”37

If indeed we stand, surrounded by violence, on the precipice of peace—the storm before the calm, if you will—then this book stands to be more relevant than ever.

In the interest of full transparency, I will admit here that the subtitle begins with the word “How,” which I have not included in the quotation for the purpose of sentence flow.

Literal, “The War of Return”.

Schwartz and Wilf, The War of Return, 55

As you read this review, you may find yourself confused, thinking: “These citations seem to imply that War of Return has thousands of pages. That seems unlikely.” You would be correct. I read War of Return on a Kindle, and thus have had great difficulty finding stable page numbers. Instead, I have provided a “location.” You may ask yourself: “How do I use a location?” To which I respond, “This is a question for Amazon.” For now, I will simply apologize in advance.

Schwartz and Wilf, The War of Return, 131.

Id. at 148.

This is just definitional—you’d get outvoted. You can also look at historical examples: there was no self-determination by Jews in Arab countries, or the United States, or anywhere else that Jews lived. One needs a majority.

Schwartz and Wilf, The War of Return, 761.

Id. at 2448.

Id. at 2961.

It is left unaddressed how fledgling Israel would have handled a much larger Arab minority. In the modern day, Israeli Arabs make up around 20% of the population.

Schwartz and Wilf, The War of Return, 387.

Id. at 436.

Id. at 907.

Id. at 416.

Id. at 496.

Id. at 1398.

Id. at 2961.

Id. at 1631.

Id. at 1329.

Id. at 1474.

Id. at 1953.

Id. at 2248.

Id. at 3559.

Id. at 3785.

Id. at 3516.

Id. at 2065.

Id. at 2496.

I would like to note, at this point, that there is a lot more to say about UNRWA. In fact, there are probably several books worth of things to be said about UNRWA. If you want to read one such book, you should definitely read War of Return! There are comparisons of budget details and staffing numbers between UNRWA and UNHCR, analysis of the success of other major UN revitalization agencies like UNKRA and why that didn’t happen with UNRWA, and more. But, for the purpose of this review, we have to move on. Apologies.

I love footnotes. I especially like when they are humorous, instead of just page citations, which I realize this review—much like War of Return itself—lacks. So here is one in compensation.

Including but not limited to archives from the UN, Israel, US, UK, and Al Jareeza’s Palestine Papers, interviews with high-ranking Israeli politicians and military figures, and a wealth of books, articles, reports, and position papers from throughout the conflict’s long history.

Schwartz and Wilf, The War of Return, 3246

Ibid.

Id. at 1309.

One such adjustment, if Schwartz and Wilf are taking suggestions, would be to address the rise of the new Israeli right. Netanyahu’s current government contains a minister with a conviction for terrorism; their book was published before this latest example of extremism from the Jewish side, and I would hope an updated version would address this.

Schwartz and Wilf, The War of Return, 1006.

Id. at 3408.