Flinging an object a distance is perhaps humanity’s oldest challenge—and it’s one I faced with my teammates for the final project of ME102: Foundations of Product Realization. Building a machine to achieve this feat covers a fairly vast problem space: fortunately, we were provided with some constraints. This narrowed our work to answering three fundamental questions.

- How might we propel a ping pong ball eight feet into a 4“-diameter hole using springs?

- How might we reload after each shot (at least 5 times) without touching the balls?

- How might we do each of these tasks consistently and smoothly?

After an exhausting week practically living in the PRL, we had our answer:

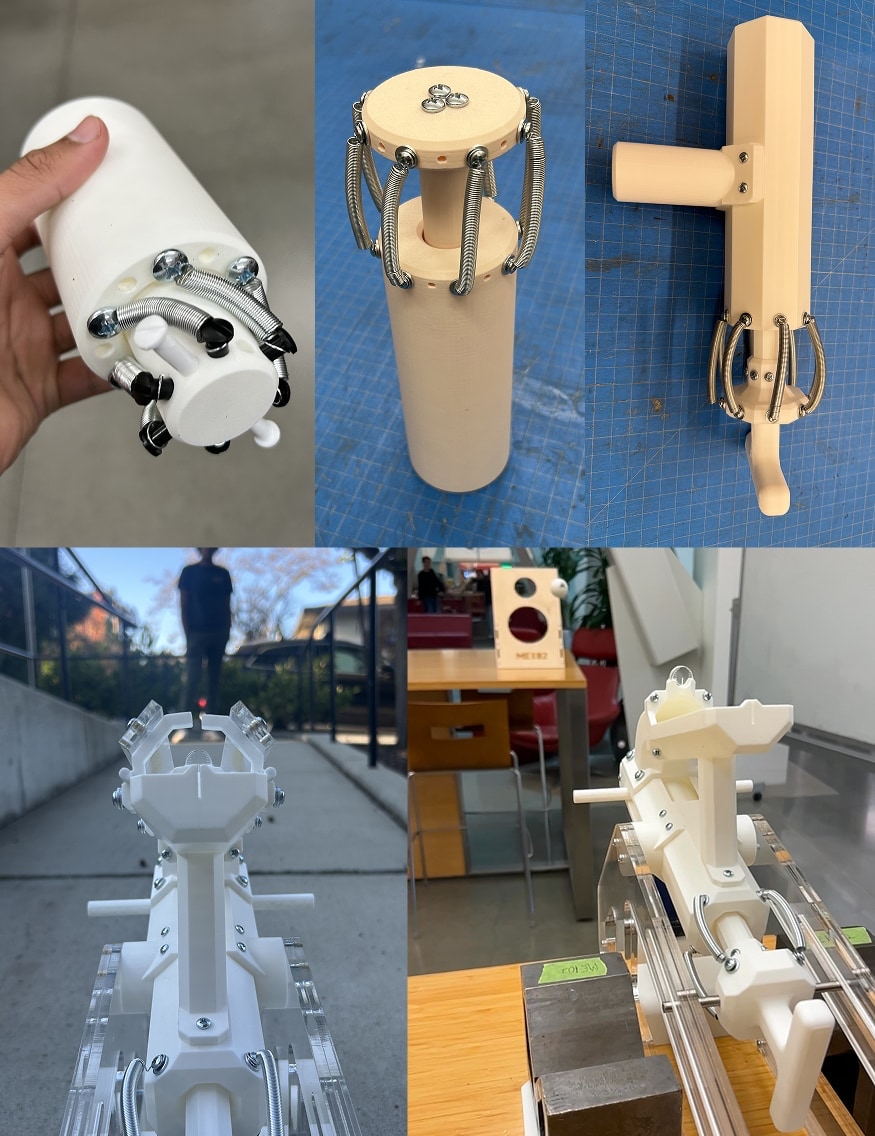

Our first three prototypes focused on the firing mechanism. Our designs evolved from a simple tube and rod system into a hand-held ping pong gun. We primarily iterated on the geometry of the barrel and housing of the springs, developing many features that would be central to our continued work: an octagonal shape, side-mounted modules, and an ergonomic handle.

Though functional enough to be fun to shoot at each other, this version didn’t quite satisfy the project requirements: our continued design work focused on mounting the system. We were particularly interested in ways that this new form could make its operation less manual and more consistent. We bounced between gear systems, levers, cranks, and several more automated release mechanisms that made the device more manual and less consistent. Observing this perplexing result, we halved the number of springs (down to four, which yielded identical results in terms of distance while allowing us to simplify our launcher mechanically) and returned to the functional firing system we began with.

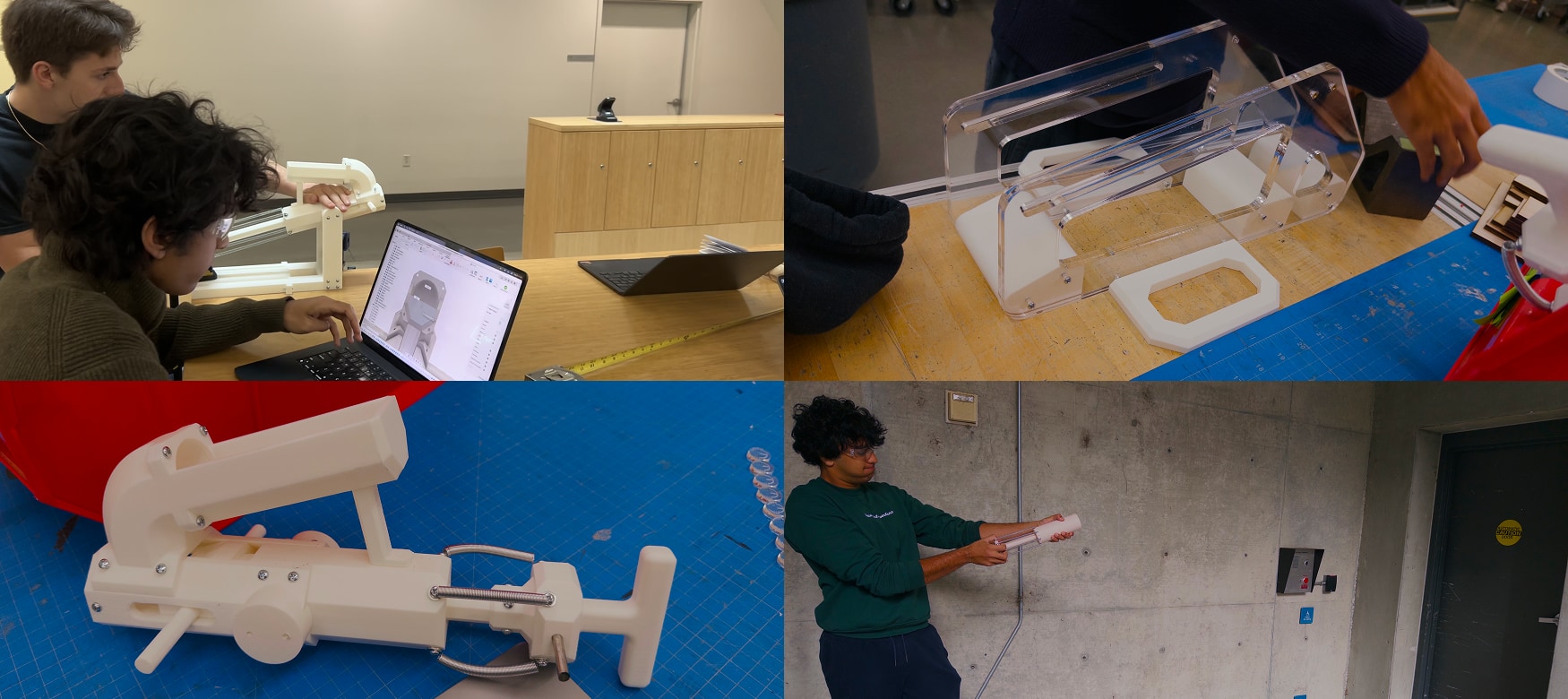

Finishing the device necessitated a whole host of upgrades: a reload system built from an inclined tube, heat-set inserts throughout the chassis, and a reimagined stand manufactured on the laser cutter rather than the 3D printer. The reservoir in the reload system has pivoting guards above it which restrict the movement of the balls within: without the protection of the guards, our extremely light ammo would be jolted out of the device by the recoil from each shot. Meanwhile, the new stand boasts a guiding track which limits the wobble of the striking rod, neutralizing the vertical and lateral variability that might otherwise arise from a combination of human falliability and machined tolerances.

Crucially, we dialed in the functionality through testing. This experimentation involved firing (and sometimes losing) whole clips of ping pong balls. We tweaked clamp and weight placements, varied the angle of the barrel, and trained to hold the handle properly in order to get a reproducible shot.

Part of what’s wonderful about working with a team you really enjoy, as I had the great fortune of doing on this project, is that the work itself becomes play. This is where real creativity surfaces. In the case of the launcher, this meant that we wanted to go beyond simply making a device that achieved the maximum performance score. We wanted something that would make us proud: it needed style.

Our first addition to that end was the projectile iron sight. This small etched acrylic circle—aligned with a small notch at the rear of the reservoir—employs the parallax effect to give the operator a direct line of sight along the ball’s trajectory. It was mostly a joke: like putting a spoiler on a Prius. But it was actually pretty useful on testing day, which was a welcome bonus!

Second, we designed the five-shot reload capability to approximate a bolt action mechanism. The handle is located by the mouth of the barrel, and physically prevents balls from descending from the reservoir in its resting position. When retracted, one ball enters the barrel, and a large chamfer on the front-facing side pushes any extra balls back into the reservoir as you conclude the loading process by returning the handle back to its extended state. The launcher is definitively non-lethal, but you hardly feel that way when you’re slamming the bolt around after a shot.

Looking at a complex machine, it can be challenging to grasp how all of its minute components form the whole. In our CAD work for this project, we developed a visceral understanding of how that understanding might happen: piece by piece. A table-mounted ping pong cannon is too big a problem to solve all at once. But chunk it up, and it becomes approachable—a barrel is a cylinder, a handle is two perpendicular rectangles, and so on. This sort of understanding is further facilitated when you avoid over-engineering things. It is tempting to look down on simple solutions. Yet these are often the most reliable! Our ultimate product uses far more of these solutions than the complex, fallible ideas we often start out with.

In iterating on the device further, we are curious about maximizing precision and consistency and minimizing size. Though this could be performed through experimentation, we want to give some attention to prior art. We are keenly interested in reading materials on the complex mechanisms we implemented (such as chambers and reloading, striking/launching projectiles, and springs in low-tolerance environments), and will seek them out before making any improvements.

We also want Timotheé Chalamet to see it and use it in the promo for his new movie.